For the past six months I’ve been using the Light L16 camera. I first learned about and preordered this camera in October 2015, and after a two year wait finally got my hands on it.

Let me start by saying that the L16 does not yet support video recording, direct uploading to social media, sharing to iOS devices, high dynamic range (HDR) photos, exposure bracketing, optical image stabilization, and some other features found on high end DSLR and smartphone cameras. Many (but not all) of these features are promised in future software updates.

The camera has quite a few limitations and is best suited to early adopters who are willing to put in the time/effort to get the most out of it. Having said all of this, I like it and have decided to keep it. More importantly, six months down the road I’m finding myself using it more and more. Here’s why.

Introduction

The L16 is more closely related to a smartphone than a traditional digital camera. It is an Android based device with sixteen mobile phone grade camera sensors (13 megapixels each) each with their own lens of varying focal lengths (28mm, 70mm, and 150mm). The camera combines up to ten of these sixteen sensors to produce a photo.

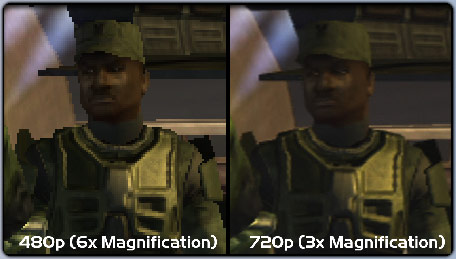

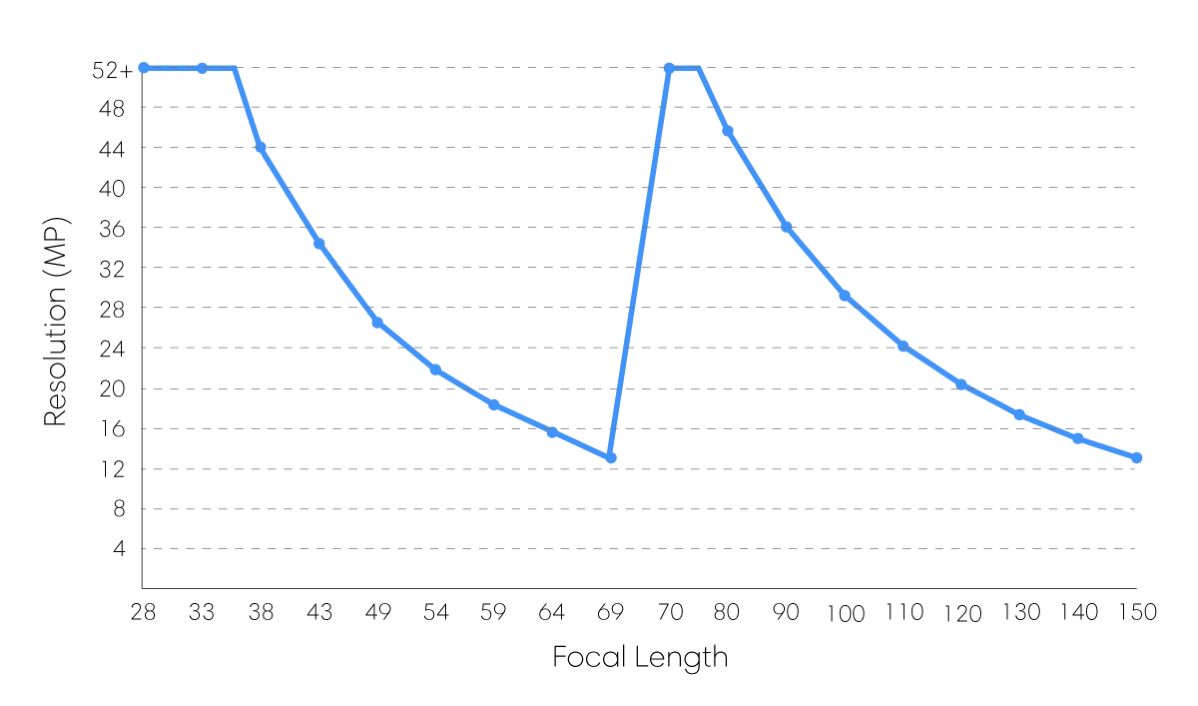

Depending on the focal length you select, the camera generates an image of between 13-80 megapixels. The “prime” focal lengths are 35mm, 75mm, and 150mm where you get the sharpest images with minimal interpolation. At 35 & 75mm, you get images of approximately 52 megapixels. More information on this variable resolution is available on the Light website.

The L16 is a computational camera, meaning that the photos it captures are generated by software algorithms processing data collected by its sensors. This means that it’s performance depends on the quality of camera firmware and image processing software. The hardware obviously doesn’t change, but it’s software changes frequently unlike traditional digital cameras. With each software update the functionality, image quality, reliability, and performance of the camera changes (hopefully improving).

The L16 today

Today, the L16 is a product with solid hardware and beta-quality software. Not all features work as advertised, the camera has some bugs related to capturing images, the desktop software is changing rapidly and requires significant CPU performance, and it’s not yes seamless to capture and share images online. Having said that, if you are willing to overlook these issues and put in the effort to post-process images after they are captured, the camera can produce some amazing results.

L16 Images & Workflow

L16 Images & Workflow

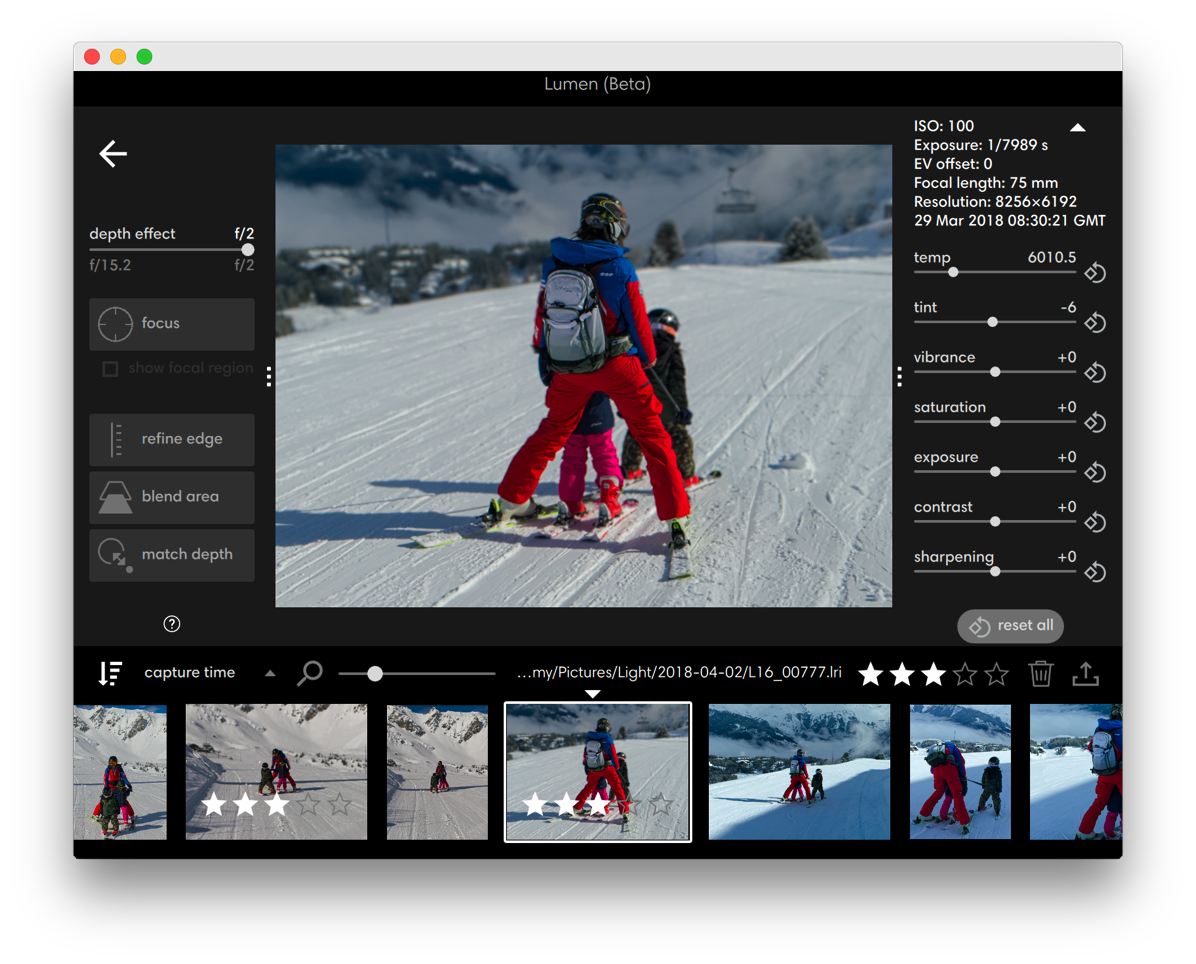

Lumen is used to combine the multiple exposures the L16 captures and provide some controls over how that happens and do some basic edits to the final image. The camera captures images as a LRI (Light Raw Image) file, which is basically a container that includes the images captured by each sensor and some metadata to aid merging.

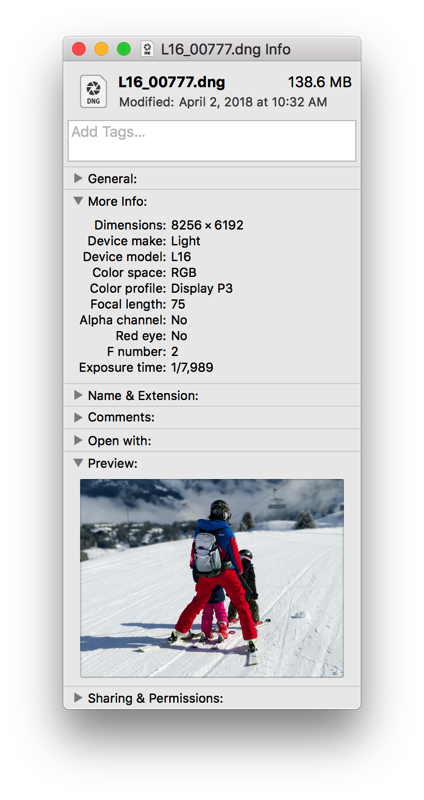

You can output your image at various resolutions and in either JPEG or DNG format. In my case, I always elect to output full resolution DNGs that I then edit further in Lightroom. To the left you can see the file details for a typical full resolution DNG outputted from Lumen.

In my case, my workflow involves Lumen, Lightroom, and Apple Photos. From Lightroom I output 16-bit TIFF files with Display P3 colorspace that are then pulled into Photos as my main photo management tool. The challenge is the large amount of storage space that each image takes: approximately 200MB RAW + 150MB DNG + 230MB TIFF = ~580MB total disk space per image for my workflow. I plan to implement an AppleScript to automatically archive the LRI and DNG files once I’ve processed my final image.

As mentioned earlier, processing L16 images in Lumen is quite CPU intensive. I use it on both my 2013 Mac Pro (3.5 GHz Intel Xeon E5, 6-core) and a 2016 MacBook Pro (3.3 GHz Intel Core i7, dual-core). Exporting full resolution DNG files can be a very time consuming process that maxes out all cores on my machines. I haven’t had a chance to test Lumen on a machine with a larger number of cores (like the 2017 iMac Pro with an 18-core Xeon), but I suspect that the process will benefit from being able to parallelize the export process across a larger number of cores. I don’t anticipate that Light can do much to speed up this process beyond a certain amount.

Taking Photos with the L16

The process of taking photos with the L16 is similar to that of a modern smartphone, but with additional options tailored to more professional users. The L16 has a nice touchscreen on the back that is used to compose the shot and adjust camera settings. There are two main parts to the software: a photo capture function and an image gallery.

The camera currently supports the following capture modes: automatic, ISO priority, shutter priority, and manual control. It also has a self timer, burst mode, white balance adjustment, and exposure compensation adjustment. In the gallery view, you typically see a low resolution preview from one of the ten sensors used to capture the image. You can optionally generate a higher resolution preview in-camera that combines images from five sensors. Aperture adjustment is currently done in Lumen and by default all photos are captured at the equivalent of f15. There are basic photo editing tools in-camera

It can be a bit frustrating at times to not have hardware buttons for zoom, but the camera body does have touch sensors that appear to be for this purpose that are yet to be enabled in software. I hope this happens soon. Currently zoom is achieved by swiping your finger up and down over the preview image.

One drawback of the touchscreen is that it’s not bright enough when shooting outside in bright sunlight. The camera itself is not waterproof or splash resistant, and the touch screen doesn’t always respond to touch inputs if there are drops of water on the screen.

Is it a good camera?

After detailing the features and drawbacks of the L16, I want to talk about what is probably most interesting and relevant to anyone reading this review: is it better than modern smartphone cameras? Sometimes.

If I’m taking regular photos of my family and daily life for sharing on Instagram or other social media, I prefer to use my iPhone X. If I’m taking photos that I might use in other ways that benefits from more resolution, photos that would benefit from greater zoom, or photos of complex scenes with both bright and dark elements, and when I have time to process the resulting images on my computer, then I prefer to use the L16.

Let me give you a specific scenario in which the L16 was the best camera for the job: skiing. On a family ski holiday last month to Courchevel, I wanted to have a camera that fit into my ski jacket, had sufficient zoom to take compelling portraits and landscapes, and enough resolution to display at larger sizes. My other camera (iPhone X, Leica Q, Panasonic LUMIX FZ1000) were not suitable and the L16 performed admirably.

I was able to capture good photos in challenging conditions: cold, very bright, not easy to compose shots, limited space in my jacket pocket, multiple falls without being damaged and without damaging me. My iPhone X could have been used for some of these shots, but many times it lacks sufficient zoom and resolution to take quick photos and then crop to desired size later. With almost 4x the resolution and optical zoom in a pocketable format, the L16 worked out well on this trip.

Another feature of the L16 is the ability to add a depth effect to image, similar to the Portrait mode on the iPhone X, after the image is taken. You can adjust this depth effect to emulate a depth-of-field down to f2. Here is an example of the original image and the same with depth effect applied:

As is the case with the iPhone X’s Portrait mode, the L16 depth effect is not perfect and often requires using editing tools in Lumen to correct errors. I’ve not been able to get the hang of those tools, so I use the depth effect sparingly. I’m spoilt by the f1.7 aperture on my Leica Q and so most simulated depth-of-field effects don’t look very appealing to me.

Other areas where the L16 excels is landscape, urban, and architectural photography. It’s compact size means that it’s more likely to be with you when you see something interesting, and it’s resolution and optical zoom gives you flexibility to frame your phone quickly. Another feature is the impressive detail that can be recovered from the highlights and shadows…rivaling professional DSLRs in some cases. This is because the current version of the L16 software includes a wide dynamic range (WDR) feature that underexposes one of the sensors when capturing a scene. The DNG file brought into Lumen can recover a lot of detail from highlights as a result, and you can safely expose photos for the shadow areas knowing that blowout highlights are not as much of a problem as typical cameras. A simultaneous HDR mode is promised for a future software update.

The resolution when capturing photos is apparent in this comparison of an iPhone X HDR photo vs. the L16 WDR photo of the same scene (sunrise in Singapore):

And here is the detail available from each camera when you zoom in on the SingTel building in the background:

Not only is there more detail in the L16 photo on the right, but far less noise. At Instagram image sizes you can’t really appreciate these details, but when you look at the two photos on a large computer monitor, 4K TV, or large print you can definitely see the difference.

There are two situations where L16 image quality needs improvement: high ISO (above 1,000) and certain focal lengths where more interpolation is required. The lack of optical image stabilization makes the low light noise problem a bigger issue than on other cameras. If you can use a tripod or place the camera on a flat surface, it’s possible to get clean low-noise photos by using ISO priority mode and setting it to 100 or 200. Handheld, the iPhone X performs noticeably better at low-light photography.

Show me the goods!

OK, enough chit-chat and let me show you some of the photos that I’ve taken over the past six months with the L16 so you can judge it’s quality yourself by looking at my collection L16 albums on Flickr. You can pixel-peep at the full resolution images there, but I’ve included some at the end of this post.